A History of Frieth |

Pillow Lace - as told by Peggy West |

|

Preface |

[ This piece was written by Peggy West in

about 1980. It is also included in Valerie Springett's book "The

Firm - Peggy's Memories Revealed". Peggy lived at

The Firm and was a lacemaker all her life and taught the

craft to a number of girls. She was also the Sunday School teacher when I was a child and 'Brown Owl' for the Brownies. She passed away in 2006 ]

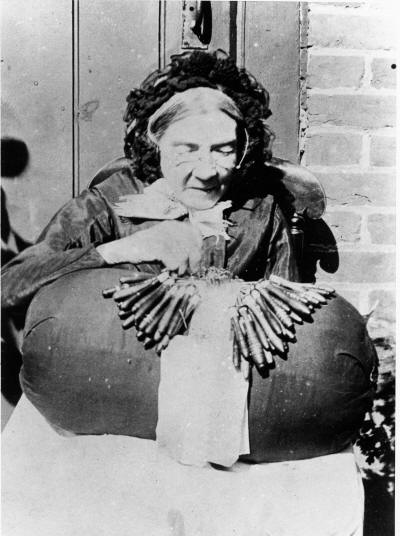

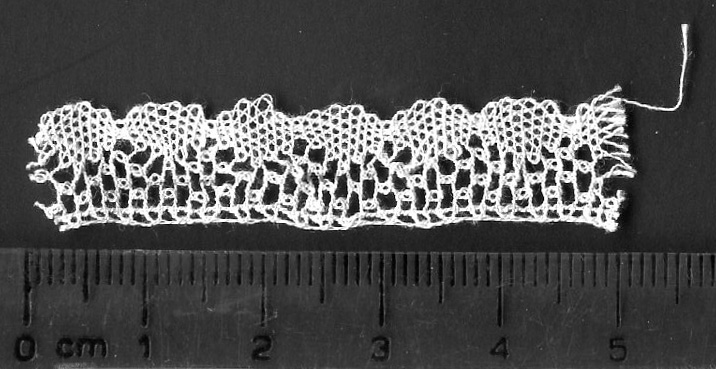

I have been asked to tell you something about Bucks lace-making. How the craft came to Bucks is somewhat speculative. Many think it was brought by the Flemish as some of the very old designs are Flemish. On the other hand tradition says it was introduced to the peasants of Bedfordshire by Queen Katherine of Aragon. Around 1600 lace-making was the chief industry of Marlow and the villages around. A few years later a change of fashion, using no lace, ended the lace trade and brought great poverty to Marlow and district. It was at this time, 1626, that Sir William Borlase founded the school that bears his name. It was for 24 boys to learn to read and write and cast accounts and 24 girls to knit, spin and make bone lace. At Marlow the lace trade again flourished, and continued to do so in the villages around, gradually dying out as machine made lace became popular. I am glad to say that at the present time lace making is again becoming popular and many more people are learning the old craft. Here in Frieth about 150 years ago [ i.e. about 1830 ] lace was made in most of the cottages. It was taught to the small girls in lace schools. Before the school was built in about 1865 there were 4 lace schools and 2 combined lace and Dame schools in different cottages.  Mary Martin a lacemaker who lived at The Cottage, Little Frieth One Dame and lace school was in the house where Mrs. McNeil lives [ Flint Cottage Rear ], this was run by Mrs. West, later to become the first Head of the new Frieth School. The other was at Little Frieth, in the house by the footpath called Folly Cottage [ now known as Chilterns ], known to most of us as Bess Janes' Cottage. This school was run by the owner of the cottage and his wife, great-great-grandparents of Mrs. McNeil. I have a letter from their great-granddaughter telling me a little about that school. One night the school was broken into. The lace was cut off all the children's pillows and the school bell was stolen. The bell was found later thrown into the hedge along Little Frieth lane. We all know that bell, for years it was used to call the children into Frieth school and it is still there. The lace schools were at Spurgrove, Perrin Spring and Little Frieth. The Spurgrove one was in the house now called Willems. This was in charge of Mary Ann Barlow, one of the very skilled lace makers of this place, whose work was sometimes taken to London by Mrs. Alfred Cripps for exhibition. West's Cottages at Perrin Spring were until quite recently 3 cottages. The middle one was a lace school. It was in this cottage that lace was made for Queen Victoria at the time of her wedding. There were 3 cottages in what now is Creighton Cottage and also 3 in what is now Folly Cottage, both at Little Frieth. In each of these rows were lace schools. I think Ann Humphries taught one, the other I do not know.  Mary Clark (nee Barlow) The children started at the lace schools at the age of 4 or 5 and had to work long hours. They were expected to move 600 pins an hour. when I was in practice and working all out, I could move 500 in an hour, but only for a short spell to see how fast I could go. The children were supposed to do it daily for 5 days a week. On Friday evening the children stacked their pillows and stools along the wall and were free until Monday morning. A child getting its bobbins muddled was very likely to get its nose pushed down hard onto the pin heads , I learned lace making from Mrs. Poole, who lived where Mrs. Ing does now. I was 6 and my sister 5 when we learnt. We sat on low stools, one each side of Mrs. Poole, she worked at her pillow whilst keeping an eye on us. From her I learned much of what I know about lace schools, for she learned in one many years before. When we got into a muddle, which was often, she got really irate and snapped, "Drat you, if you ain't got they bobbins aggled again, I'll have to get that there old Cat-stick to you yet", she never did, but I gathered that the threat of "that old stick" was no idle one in her young days. It took me 5 or 6 weeks, 3/4 hour each day to learn the first pattern. When I took my pillow home I did as much as I liked each day. When a child from a lace school took her pillow home she had to do a certain length before being allowed out to play. One woman told me she had to work all round her pillow, about 28 ins. before she went out, she could not have had many hours to play.  A small piece of 'Rosebud' pattern lace made by Peggy West The women's earnings from the lace was a great help towards the family budget in those days. The price of the lace varied according to the pattern, from 6d to £2.2.0 a yard, the average earning of a worker was about a shilling a day. A lot of the lace was sold in Marlow, also local people ordered it. Mrs. Brown told me that she had heard from her mother-in-law that the owner of a Grocer's shop in Lane End would collect lace in exchange for groceries, I wonder what sort of profit he made. Bess Janes used to make wide flounces for Miss Cripps at Parmoor. The Misses Johnson of Lane End tried to keep the industry going. They would collect lace and sell it for the women, they would also buy cotton, either black or white, in Wycombe for the women. The shop selling cotton was Ruttys, a draper. I got my cotton there until it stopped selling lace making things. The shop was taken over by Rivetts and now is Murrays. We now have to send to Braggins in Bradford to get lace making equipment , My pillow was made by Ken Hobbs, his first effort, and a very successful one. It used to be possible to buy pillows in West Wycombe, from a saddlers shop, they were strung up outside the shop. It is now a butchers shop. I have quite a collection of pillows on which miles of lace have been made. They were given to me by relations of the old lace makers. One is a great treasure, it belonged to Mrs. Susan Brown. I spent many happy hours watching her working on it and hearing her tell of days gone by. Another, which came from Lane End was almost in two halves, so soft had it become round the middle from the millions of pins that had been stuck in over the years. I also have a large collection of pasteboard patterns, many very old. These came from a lace school at Hambleden, given to me by a grand-daughter of the teacher.

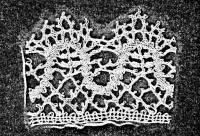

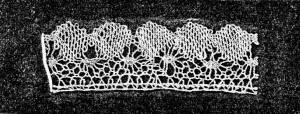

'Maltese' and 'Spider and Fan' patterns The Bobbins are works of art. Most are made of wood, but bone was also used, hence one of the names for pillow lace, "bone-lace". The men used to make bobbins. I have some with names or loving messages burnt on. In those days they "said it" with bobbins instead of flowers. The ideal place to make lace is outdoors, it is the best light. In the summer the women would sit on their doorsteps and work at their pillows. In winter the light was either a dim oil lamp or, more often, one candle. Sometimes the candle was aided by a glass bottle, round, filled with water, called a candle lamp and this would magnify the light. One of the lacemakers told me that they used to meet in each other's cottages in turn to work, and so save fuel. Each would take along a pinch of tea leaves as a contribution to the "brew". How I should love to have been present on one of those afternoons listening to the lovely sound of hundreds of bobbins clicking and the tongues going in broad Bucks telling the local gossip. I remember Mrs. Harris' brother talking about his mother who was a great lace maker. He said "we got so tired a-earing her a-clicketting they bobbins". He also said "I used to watch her a-wickering they bobbins round they pins I never knew how she kept they straight. She'd just push one bunch back and grab another lot, she never seemed to stop to look". Watching a real lace-maker at work is wonderful, her left hand is continually moving bobbins, back, forth, over, under whilst her right sticks in the pins. The rhythm of the clicking bobbins never ceases until a thread breaks or a bobbin runs out. It is a quite unforgettable memory, the music of the bobbins, and sad to say, a lost joy for a modern worker cannot get the same rhythm. Only those who learned at the age of 4 or 5 and worked on for 70 or 80 years could get that unforgettable music from the bobbins. |